Mad Mags Magnet Car Art State of Love Bride 2b

from the magazine

Where There's a Volition

William Erwin Eisner, the father of the graphic novel

Leap 2013

© WILL EISNER STUDIOS, INC. THE SPIRIT TRADEMARK IS OWNED Past WILL EISNER STUDIOS, INC. AND IS REGISTERED IN THE U.S. PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE. IMAGES PROVIDED By DENIS KITCHEN ART AGENCY/Www.DENISKITCHEN.COM

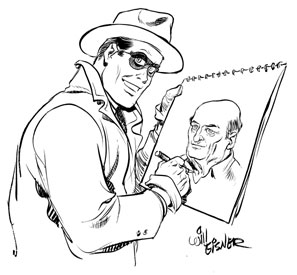

Eisner's near famous character, the Spirit, draws his creator.

DeWitt Clinton High Schoolhouse in the Bronx boasts more than 200 globe-renowned graduates, including playwrights Paddy Chayefsky and Neil Simon, actors Burt Lancaster and Judd Hirsch, Broadway composers Frank Loesser and Richard Rodgers, manner designer Ralph Lauren, and congressman Charles Rangel. Compared with these figures, Will Eisner scarcely registers in the public mind.

Yet this 1936 graduate is slowly becoming the near influential of them all. Throughout the world, he'south now acknowledged equally the father of the graphic novel. Not that he invented the genre; others preceded him. Simply none had his mastery of sequential art—the ability to tell a human story in convincing, compelling pictures and dialogue.

A child of Jewish immigrants, William Erwin Eisner saw himself as a 50-50 amalgam of maternal and paternal genes. His mother, Fannie, whose parents had fled the pogroms of Romania, was a applied sort. She agreed with President Coolidge: the business organisation of America was business organization. Her husband, Sam, who hailed from Vienna, dreamed of an artistic career in the New Earth. As it turned out, he spent his life painting scenery for vaudeville and Yiddish theaters—when he could discover work.

Will, the eldest of their iii children, was born in 1917. He showed his skills early on, doodling in detail when he was barely out of the high chair and afterward providing bright illustrations for the school newspaper. By the time he was a student at DeWitt Clinton, the shadow of the Low had fallen across America. Sam Eisner saw his few remaining dollars disappear in a banking concern failure. Will was haunted by the surreal attribute of "people in Chesterfield coats with velvet collars and a nice bowler hat, good shoes, standing in Wall Street with an orange box selling apples at five cents each. These were weird, about theatrical scenes. People who had a car in the yard, a very adept car, which they couldn't drive because they didn't take the coin for gasoline. They couldn't sell it. And anyhow they didn't want to give it upward. Some kind of times. They helped shape your outlook."

Yet even in New York Urban center's darkest moment, in that location came a flicker of promise. Every bit lurid magazines faded, a new kind of periodical was rising to take their place—the comic book. That name was a misnomer: just every bit the paper "funnies" of the menstruation, such equally Dick Tracy and Tarzan, featured rip-roaring adventures, the comic books featured the exploits of humor-costless heroes and heroines. Eisner was interested in joining the ranks of comic-book artists, only when he made the rounds of magazine publishers, he met a series of refusals. But Jerry Iger, the thirtysomething editor of a new tabloid-size comic book, Wow, What a Mag!, was willing to roll the die with the brash, talented kid. He hired Eisner to draw and write his own strips. One of them, Captain Scott Dalton, focused on a dashing pursuer of rare artifacts, anticipating Indiana Jones past fifty years.

Alas, the underfinanced Wow lasted for only four problems. Down to his last $30, Eisner was desperate enough to consider all offers. I of them, he recalled, came from a mafioso "complete with little finger ring, cleaved nose, black shirt and white tie, who claimed to have exclusive distribution rights for all Brooklyn." The thug offered Eisner three bucks per folio to illustrate "Tijuana Bibles"—X-rated versions of established comic strips, with the protagonists shown in explicit sexual escapades. Eisner considered the offer for several days before declining information technology. He called the refusal "ane of the near difficult moral decisions of my life."

At this signal, Eisner was down, and Iger was out. The departure between them was that Eisner had merely begun to dream. In 1937, he persuaded his ex-boss to go into concern with him as a packager, selling comic strips to newspaper syndicates and comic books to Trick Comics, Fiction Business firm, and other publishers. Iger would handle the marketing; Eisner would be in charge of the writing and drawing. Financed by Eisner, they rented a fiddling room in Tudor City, in midtown Manhattan, and put EISNER & IGER on the door. A year before, and the Depression would accept discouraged clients from taking a chance on the new business concern; a twelvemonth later, and at that place would have been besides much contest. As it was, the fledgling visitor's efforts were reasonable ($5 per page), executed with flair, and promoted with vigor. At offset, Eisner was not only the head artist and writer but the just i, churning out five unlike comics under v dissimilar names, among them Erwin Willis and Willis B. Rensie ("Eisner" spelled astern).

Every bit sales increased, fees rose and employees were taken on. Bob Kane (né Kahn), another son of Jewish immigrants, was hired to illustrate a Disney knockoff called Peter Pupp. He soon departed to describe an adventure comic named for a dissimilar mammal, becoming the creator of Batman. Amidst Eisner's other hires was the 17-twelvemonth-former Jacob Kurtzberg, who became Jack Curtis and after, when he left the visitor, Jack Kirby. Nether that moniker, he helped create a series of superheroes, including Captain America, the Incredible Blob, and the 10-Men. Eisner wasn't a flawless talent scout, nonetheless. When Joe Schuster and Jerry Siegel mailed in some ideas for a new strip, he turned them down common cold—telling them, he afterward remembered, that they "weren't prepare to come up to New York" and that "their way wasn't professional yet." And so, writes Eisner's biographer, Michael Schumacher, "in one of the few giant missteps in a career characterized by strong instincts and judgment, Bill Eisner shot downwardly Superman."

By 1938, Eisner had created or supervised scores of strips. One of them—Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, featuring a zaftig blonde in a tight-fitting leopard skin—had future lives on film and TV. Some other, Hawks of the Seas, featured an Errol Flynn–like buccaneer two years before Flynn starred in The Sea Hawk, a film unrelated (officially, at any rate) to Eisner'due south strip. To assure highbrows that Eisner & Iger could take the elevated road when it wanted to, the company also produced literate comic-strip versions of The Count of Monte Cristo and The Hunchback of Notre Matriarch.

By 1939, Will Eisner was well-off and, in the pocket-size world of comic books, famous. And then famous, in fact, that he was approached by i of his clients, the Register and Tribune Syndicate, which saw the ascent popularity of comic books on newsstands and came up with a revolutionary idea. What if Eisner drew and wrote his own four-colour, xvi-folio comic volume—non sold individually, every bit the other comic books were, merely folded into the Lord's day edition of iv major newspapers? He would reach a potential audition of ane.5 million readers. The offer was generous and flattering. The problem was that creating and managing such a project would be a full-time job; Eisner would have to leave the company that he had cofounded.

Iger warned his partner: "You're stupid to practice this. Yous're 21 years old, and the war's coming on and yous're going to exist drafted. . . . You lot're going to exist back to running around with a blackness portfolio when the war is over. If you survive." But Eisner, beguiled by the notion of creating a new kind of comic book, wasn't listening. Looking back, he recalled, "I sold the visitor for buttons, really. Peanuts." Iger offered $20,000; Eisner took the peanuts and ran.

He rented a larger apartment in Tudor City and set up shop with several assistants to help write and describe his new comic book, which he called The Spirit. Eisner disliked the idea of a steroidal hero on the order of Superman, Batman, or Captain Marvel. He wanted his protagonist, Denny Colt, to exist credibly human, still endowed with Sherlockian vigor and intellect. Over the course of ii weeks, he came up with a backstory. Filly had been a devil-may-care policeman until he did battle with the maniacal Md Cobra, who was about to poison New York City'south reservoirs. Colt, confronting him, received a lethal dose of the formula—or then everyone thought. Actually, he was only in a state of suspended animation. Post-funeral, he awoke in his grave and realized that fate had granted him a new career: he would exist a freelance crime fighter, beholden to no one but himself. Acting alone, he constructed a secret lair beneath his burial vault. . . .

All very well, harrumphed Eisner's new employers. But what's and then special most this Denny Filly?

Fluently advertising-libbing, Eisner replied, "He's got a mask."

"That's adept." But what else, they insisted?

"He's got gloves and a bluish suit."

In an age of caped crusaders and men of steel, these were meager assets for a offense fighter. Merely Eisner's creative and narrative skills were already legendary, and the syndicate took a risk on them—a gamble that paid off in spades. The Spirit was rendered with unusual realism. Unlike most strips, information technology had atmospheric condition. Pelting (known in the trade equally Eisnerspritz) would pelt downward, staining the sides of buildings drawn with scrupulous precision. Wind would whip through city streets, carrying scraps of paper and palpable grit. The protagonist echoed the jaunty mental attitude of Cary Grant rather than the humorless manner of the men from Krypton and Gotham. At his side was his trusted aide Ebony White, an African-American cabdriver. In addition, The Spirit boasted an intelligent love interest, rather than the customary wide-eyed bimbo: Ellen Dolan, the police commissioner's daughter. Dolan was ambitious plenty to run for mayor only vulnerable plenty, naturally, to need rescuing at present and then.

The Spirit's greatest asset was its creator'due south technical prowess. "I grew up on the movies," Eisner noted. "That was my affair, that'due south what I lived on. It gradually dawned on me that films were nothing simply frames on a piece of celluloid, which is actually no different than frames on a piece of paper." As Eisner saw information technology, he was the director, costume designer, lighting man, and cinematographer of a weekly film noir. Wide angles, close-ups, lap dissolves, and fadeouts were all office of his repertoire. No contemporary popular creative person was as ambitious, and none was every bit visually literate.

Past 1941, The Spirit could exist read in 19 major newspapers with an audition of some 3 million. That yr, when a daily version began, the Philadelphia Tape reported a typically ebullient prophecy of Eisner'due south: "The comic strip, [Eisner] explains, is no longer a comic strip but, in reality, an illustrated novel. It is new and raw in form merely now, simply material for limitless intelligent development. And eventually and inevitably it will be a legitimate medium for the best of writers and artists."

Just equally the aspiring novelist was about to striking his stride, some other prediction came truthful—Iger'south. In 1942, Will became Private William Eisner. His reputation had preceded him, still, and his orders were to create a new kind of comic book. Until then, army manuals had been marred by incomprehensible instructions and ungainly diagrams. Eisner came up with Joe Dope, a soldier who could talk to GIs in their own linguistic communication, showing them the value of preventive maintenance in lucid and agreeable pictures. After a couple of readings, the conscripts understood how their equipment functioned and how to keep information technology in peak condition.

It was impossible to work for two masters, then while he was in uniform, Eisner handed The Spirit to his staff, who kept it going until his return to civilian life in 1946. The writers and illustrators were a capable bunch: Wallace Wood became a superstar at Mad magazine, and Jules Feiffer later received a Pulitzer Prize for his Village Vox cartoons. But they didn't have the main's panache and visual mode. In his classic history The Neat Comic Book Heroes, Feiffer acknowledged that his old dominate was sui generis. Eisner'southward work, wrote Feiffer, was reminiscent of German Expressionist films, with their stark backgrounds and striking angles. His line "had weight. Clothing sabbatum on his characters heavily; when they bent an arm, deep folds sprang into activity everywhere. When one Eisner character slugged another, a existent fist striking real flesh. Violence was no externalized plot do, it was the gut of his style. Massive and indigestible, information technology curdled, lava-like, from the page. Solitary among comic book men, Eisner was a cartoonist other cartoonists swiped from."

For all its excellence, though, the spirit began to drain out of The Spirit when Eisner returned. All through his twenties, he had been an all-work, no-play kind of guy. At present he dated frequently and fell in love several times—though the only commitment he made was to his new visitor, American Visuals. Initially, Eisner intended to produce and distribute a fresh series of comic books. Kewpies would aim at the Mickey Mouse oversupply (a former Disney artist designed the characters). John Police force was to be a detective with an eyepatch and 20-20 insight. Baseball Comics would center on players of the Summer Game. None of these projects came to fruition.

Nonetheless, American Visuals turned out to be highly profitable. For along with the abortive comics, the company produced education and safety manuals for Eisner'southward old customer, the army. At one point, Eisner traveled to Korea to become a firsthand knowledge of GI requirements. During the trip, he wrote, "A big guy with a dead cigar in his rima oris came up to me, poked his finger in my chest and asked, 'Are you Volition Eisner?' I said I was, and he said, 'You saved my ass.' His tank had broken down in a combat state of affairs, and he used material from one of my stories for a field fix, and it worked and he was able to drive to rubber." The company as well turned out booklets and advertising textile for a long line of baddest clients, including RCA Records, General Motors, New York Telephone, the Baltimore Colts, and the American Red Cantankerous.

© WILL EISNER STUDIOS, INC. IMAGES PROVIDED BY DENIS KITCHEN ART Bureau/Www.DENISKITCHEN.COM

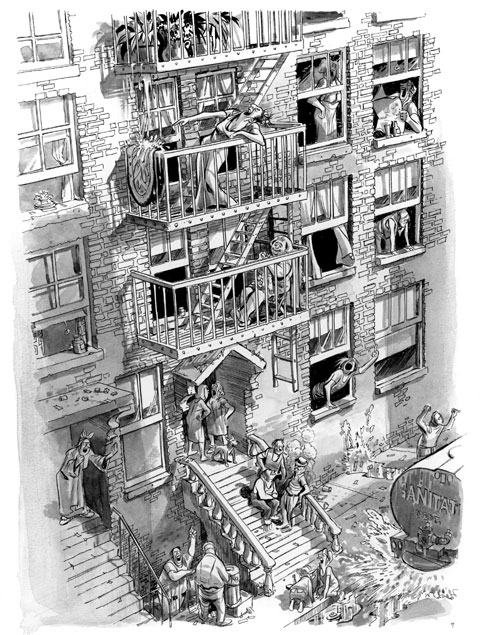

Eisner considered himself a director, costume designer, lighting human, and cinematographer on the illustrated page.

In the belatedly 1940s, Eisner finally got serious about ane of his dates. Ann Weingarten was the girl of a prosperous and wary stockbroker who feared that the 34-twelvemonth-old young man was a fortune hunter. "We found out later that my father had Will investigated," Ann remembered. "Was he a reputable person? Did he steal? I was furious when I found out, simply Will said, 'Why not? Permit him look me up. I haven't done anything bad.' " Just then, and Mr. Weingarten, impressed by Eisner'southward profits if not his profession, agreed to give the bride abroad. The couple married in June 1950 at Temple Emanu-El, the largest synagogue in the globe, on Manhattan's Upper East Side. The reception took place at the Harmony Club. William Erwin Eisner had come a long mode from the Tijuana Bible Chugalug.

The increasing prosperity of American Visuals left no time for The Spirit, and Eisner let it elapse. The last episode appeared in October 1952, not long afterwards the nascency of the Eisners' first child, John. A daughter, Alice, was built-in a year and a half later on. Relocated to a big house in White Plains, the family lived a quiet suburban life. The artist who had gear up the standard for comic books had go a businessman, forgotten by all but a few collectors and cognoscenti.

His timing wasn't bad. A psychiatrist named Fredric Wertham had been traveling around the state and denouncing comic books as a font of juvenile delinquency. Seduction of the Innocent, his 1954 treatise, laid out the argument in item. In Wertham's view, comic books encouraged racism and violence, Superman was a fascistic creature, Batman and Robin amounted to a "wish dream of two homosexuals living together," and Wonder Adult female was into chains. Senator Estes Kefauver, fresh from his televised investigation of organized crime, conducted a new hearing. This one concerned comic books, with the doctor as a key witness. The public reacted with shock and revulsion; while their backs were turned, this lurid trash had been corrupting their children. Thus was born the Comics Lawmaking Authority, the publishers' cocky-censoring organisation, modeled on the 1930 Hollywood Production Code. Gone were instances of gross violence equally well as any hint of steamy sex. Just the damage had already been done; comic books were at present looked upon as a disreputable, back-aisle enterprise, and sales hit a new low.

The road to redemption took 15 years to build, and, even then, it was a narrow thoroughfare, consisting more often than not of underground piece of work such as R. Crumb's Caput Comix and the nose-thumbing parodies of Mad. Simply in 1965, The Great Comic Book Heroes took the loftier road, and, noted Feiffer, "the form gained a new charter on life and new respect, none of which interests me particularly, except in what I did to redeem Will Eisner'southward career. . . . This was a guy who was no longer heard of, was completely forgotten, had forgotten himself and was no longer doing comics. I was happy that, in a sense, I was able to bring him back from the dead or, at the very least, from exile."

Yet Eisner never actually returned from comic-volume exile. At that place would exist occasional reprints or resurrections of his early material, and he would teach classes in comic illustration at the School of Visual Arts. His last dandy works, nevertheless, were prompted not by the regard of his peers but by a personal cataclysm. In the late 1960s, his teenage daughter was diagnosed with leukemia. When she died, he was comfortless. For years, Eisner refused to speak near Alice's death to anyone outside his immediate circle.

It wasn't until 1978 that he could confront that part of his past. He chosen his graphic novel A Contract with God. The plot concerns a pious immigrant, Frimme Hirsch, who writes an agreement with God on a stone. He will live a moral life; the Lord will watch over him. All goes according to program—until he loses his adopted daughter to illness. How can this sorrow exist reconciled with the notion of a good and omnipotent Jehovah? Didn't they take a Covenant? Looking dorsum at Contract, Eisner confessed, "My grief was still raw. My heart still bled." Frimme's "anguish was mine. His argument with God was likewise mine. I exorcised my rage at a Deity that I believed violated my faith and deprived my lovely 16-year-quondam child of her life at the very flowering of it."

Hirsch throws the stone out of his apartment window and turns his back on divinity and morality. He steals money from a synagogue, buys a tenement, and becomes a tight-fisted landlord; he grows rich and powerful, but his existence loses all meaning. He determines to seek a fresh contract, restore what was stolen, and renew his organized religion. Only equally Hirsch is near to adopt a new daughter, all the same, he suffers a fatal heart attack. At that instant, the tenement catches fire. Merely lives are saved because of the activity of a dauntless boy, Shloime Khreks. As Shloime heads home, he stumbles on that long-discarded stone. He signs his proper name below Frimme'south and begins a new contract with God.

This metaphor for the Jewish experience was hardly the stuff of comic books, and, in time, it changed the history of publishing. Eisner went on to write and draw graphic short stories and novels near Depression New York, the Vietnam War, love, and the Mafia. He even ventured into literary criticism. Outraged past Dickens's anti-Semitic passages in Oliver Twist (which were farther exaggerated by George Cruikshank's illustrations), Eisner retold the story from the villain'southward bespeak of view. In Fagin the Jew, a combination of misfortune and prejudice turns an appealing youth into a career criminal. Eisner doesn't excuse Fagin, just he elevates him from caricature to human being being and makes him a credible casualty of the Victorian era.

At last, in 1988, the comics manufacture got around to recognizing Eisner's unique contributions, inaugurating the Eisner Awards to honor outstanding artists and writers. Maybe the best-known recipient is Art Spiegelman, whose graphic Holocaust novel, Maus, became an international bestseller. And notwithstanding Eisner had likewise many ideas and too much energy to consider retirement. While contemporaries were collecting Social Security, he wrote and drew two how-to books for professionals, Comics and Sequential Art and Graphic Storytelling. He died in 2005 at the historic period of 89 while recuperating from a quadruple featherbed operation. On his desk were page proofs of The Plot, an extraordinary piece of graphic nonfiction anatomizing the notorious forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

Not every critic was happy with these creations. The New Yorker, for example, constitute fault with Eisner's "over-the-topness." And the Los Angeles Times judged Eisner's narratives to exist "occasionally gimmicky and contrived." All the same, it saw "something momentous" in A Contract with God, "a magisterial quality, equally if nosotros're witnessing the nascence of a motion, a kind of aesthetic big bang." John Updike agreed with the second part: Eisner was "not but alee of his times; the nowadays times are still catching up to him."

Indeed they are. The New York Times bestseller list currently includes a section for hardcover graphic novels. Both Barnes & Noble and Amazon sell more than 1,000 titles in that genre. Under its Graphix banner, Scholastic offers a spirited defense of its product: "The notion that graphic novels are too simplistic to be regarded as serious reading is outdated. The fantabulous graphic novels available today are linguistically appropriate reading material demanding many of the same skills that are needed to understand traditional works of prose."

All this gives credence to Eisner's remarks at the 2002 Conference on Comics and Graphic Novels at the University of Florida. He informed his audience that he and his coworkers "used to experience very much like a Mama Rabbit and a Daddy Rabbit, who were running around, being chased by a bunch of dogs. They dove into a hole and the Mama Rabbit is quivering. She'due south maxim, 'Oh, this is terrible. We're doomed.' The Daddy Rabbit says, 'No, don't worry about it. Nosotros'll stay here, and in half an hour, we'll outnumber them.' I always think of that when people ask me how I felt virtually all those years of so-called struggle—sooner or later, we'll outnumber them, and I remember we're outnumbering them now."

books and civilisation

The Gross Gatsby

Baz Luhrmann'southward version loses its place.

May xvi, 2013

chapplenoteduckers.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.city-journal.org/html/where-there%E2%80%99s-will-13554.html